An Old Rebel One

Let’s start with this, a flawed masterpiece is still a masterpiece.

In my mind the album Sandinista! is inseparably linked to the night, both the settings of the songs and my relationship to it. A week before I left for Morocco I dreamt I was sailing to southern Africa on a boat with a scientist and his daughter for some unknown exploratory purpose. We traversed the nebulous ocean in that weird way time moves when you’re asleep, where hours and weeks pass in moments. In my dream I viewed the progress from above like in Indiana Jones. When we arrived down near Angola I was deeply upset to realize I’d travelled halfway across the world and forgotten my copy of Sandinista! The rest of the dream was spent returning by boat to America to retrieve it.

I took it as a sign and the next day recorded (almost) the entire triple album (double cds) on the longest blank tape I could find. Tossing it into my pack with the ol Walkman I always bring on weird trips because it’s durable and bootleg cassettes are plentiful in much of the developing world. It wasn’t a record I was really into but I try and listen to the universe when it’s knock’n.

I later read that Mick Jones said in reference to Sandinista! "I always saw it as a record for people who were, like, on oil rigs. Or Arctic stations. People that weren't able to get to the record shops regularly." The perfect road album to disappear with for awhile.

Manhattan

A week ago I woke up around 12:30 and was wide awake for hours. Resigning myself to insomnia and accepting my day was gonna be fucked. At some point, lying there the Strummer/Jones harmony on Let’s Go Crazy (So you wanna go crazy? Let’s go cccrraaazzy) became stuck in my head, like my mind offering a decent soundtrack to my declining mental health until it got to the point that I just got up and started listening to it and writing this. The song arises, decorates the dark around me and then disappears again.

“All the youth, the young generation of today, I am begging them, and I'm preaching to them and I'm selling my record, I am selling clothes, I'm selling cloth to help the young generation of England today!” A West Indian voice shouts over the sounds of the street as a calypso beat comes in, then the marimba and then the boys. The song (like so many on this album) is underrated, misunderstood and hypnotically joyful. The lyrics of the verse are delivered in a ratatat style until they slip into the melodic breakdown of the bridge (But you better be careful/ You still got to watch yourself).

At some point I fell asleep for a few hours and dreamt of I was walking in Abidjan.

It’s a record that moves and shifts time, contrasting noise and color in the same manner as in a dream. At times Disjointed, disconnected and then suddenly palpable dejavú. A large, messy, weed fueled, artist controlled creation (this was their first album where instead of listing individual credits for each song they just said “By The Clash” and the band acted as producer). You can go online and see all of the smarmy takes on it from the folks who don’t get the context but why bother. They don’t understand why the mess matters. They smirk at the band taking a pay cut to release it in its entirety rather than change their design. It’s about experiencing life not analysing it from a distance.

So why pay attention to past or present reviews? I think it’s enough to just find the intentions of the creators and build your own relationship with it from there. Alex and I spent multiple winter nights drinking whiskey, listening and dissecting different tracks on it. He was the first true champion of Sandinista! that I knew. He explained the brilliance of it in a way that changed my misjudgment. He was the first person to play Rebel Waltz for me and wax on about what the lyrics meant. The story of an outnumbered encampment of freedom fighters dreaming of a better world while fighting to their deaths against a massive enemy. A song based on a dream. It was my way into understanding the profound global messages of hope and heartbreak that run parallel through the album. “I want this to be my wedding song,” he said, and I stole that line.

Walnut Grove-Imlil

In the High Atlas Mountains, in the Amazigh (commonly known as Berbers) village of Imlil signs of spring were appearing. The roads were soft and muddy and the buds on the walnut trees had just begun to blossom. When I arrived the Bujlood festival was in full swing. The festival is traditional for the Amazigh people and follows the Islamic holiday of Eid al-Aidha. Eid al-Aidha is the feast of the sacrifice during which sheep and goats are ritualistically killed, carved up and cooked as part of massive celebration. Walking around Marrakesh a few days prior, on the day of the Eid was just blood city man, in some neighborhoods I saw throats slit right over the curb, the feast was delish though.

During the Bujlood festival the men wear the skins of the sacrificed livestock and chase kids and women around the mountain roads and village footpaths of the hillside communities. Hidden behind masks they carry sticks or sometimes a limb of the animal to try and “get” the people. Kids would gather on rooftops or nearby when they saw them coming and sing taunting songs until the creatures chased them away.

From the summit of Jeb Toubkal

I had come up a few days prior to climb Jeb Toubkal with a handful of Brits I’d met. We’d been in the hills climbing the peak for a few days and returned late in the evening sunburnt and tired. We were invited to a performance of singing and drumming as a part of the Bujlood. The town was built into the hillside so there weren’t tons of areas large enough for everyone to gather, we ended up in a courtyard type space, about half the size of a basketball court. Lit with gas lanterns and night sky above I remember being so exhausted that the singing and drumming had a narcotic effect. It all became a blur of noise and movement. Eventually I walked the path in the dark to the porch on Omar’s house where my sleeping bag was laid out.

Imlil

The next morning we traveled the two and half hours down from the mountains to Marrakesh in old, Mercedes taxis. The dashboard and the rim of the windshield were ornamented and I noticed the old tape deck. I asked the driver if I could play music (shotgun, them’s the rules) and put in the blank tape that had most of Sandinista! on. This was in part to please my new British friends but also because it was a beautiful spring day and it felt great to be alive on the planet earth in that moment. A vibrant interconnectedness. The little bass breakdown of The Magnificent Seven kicked in and rolled up my limbs before slipping behind my eyes. It was a song I’d unfairly once written off as some mid-sixties Bob Dylanesque nonsense rhyming ( I was an angry teen!!). Like it was an insincere attempt to hop on a trend more than it was “serious expression” (*adjusts spectacles). “Part of life is being able to look back and see how full of shit you were the years prior,” the Dali Lama famously once said.

Strummer & Curtis Blow

When I first got into punk I was so angry and that’s what I wanted to hear reflected back at me. Alex first played the Dead Kennedys to me on our bus, when I was in 8th grade and it was like “finally, someone is not gaslighting me!” The music validated feelings I didn’t understand, it turned that pain and anger into power so you could survive and find autonomy over your life. It’s not that I didn’t like other styles of music (I did see Jewel in concert after all) it was just that once I got that real hit of raw, fast and angry rock it was all I wanted for a time. But yeah, as I got older I saw the hypocrisy of the Punk dogma and began to love and appreciate the musicians who arose from that scene but saw it for what it’s supposed to be, a lawless, genre free, community for self expression.

NYC

Following their third album, London Calling, The Clash spent a lot of time in the States. In New York City to be precise and were witness to the rise of rap, embracing the music and the musicians. “Whatever your station is you need to play more rapping music. Because we hear none of it in England. All we have is boring old Heavy Metal.” Mick said in a radio interview. In the past they had exposed their (mostly white) audience to reggae artists through their music and as opening acts. In a similar fashion they soon had the Sugar Hill and Grandmaster Flash opening for them during their 17 show run at Bond’s casino in New York.

Before The Magnificent Seven their was no cross pollination between rock and rap (Rapture by Blondie would come out later that year). When you hear some of these songs in the future, without the benefit of context and with the whole of what followed musically already a precedent, it’s east to see why I didn’t get it at first. All the years and experience get compressed until a decade you weren’t a part of becomes just a long year. What I missed was that the Magnificent Seven had a sophisticated point far beyond clever rhyming. It expressed the numbing effect of capitalism on the human spirit through the lens of a minimum wage supermarket employee’s day. Lyrically it’s fucking stunning and what’s more impressive is the Clash never seem out of their depth or like they’re playing dress up in another genre, it’s fully a Clash song. “This is when I started paying attention.” Chuck D said.

Ring! Ring! It's 7:00 A.M.!

Move y'self to go again

Cold water in the face

Brings you back to this awful place…

….

What do we have for entertainment?

Cops kickin' Gypsies on the pavement

….

So get back to work an' sweat some more

The sun will sink an' we'll get out the door

It's no good for man to work in cages

Hits the town, he drinks his wages

And the Greek chorus of the call and response throughout (You lot! What? Don't stop! Give it all you got! You lot! What? Don't stop! Yeah!). I’ve never been sure if its the bosses/society yelling at the workers to stop talking/questioning and get back to work; or if it’s the Clash yelling to the employees to wake up and break free themselves from the cycle of distraction and exploitation. I guess it depends on the mood I’m in when I hear it. I didn’t actually intend to spend this much time on the Magnificent Seven, but it kind of encapsulates how I came to wake up.

First night back in Marrakesh from Imlil

We left Imlil, snaking down the single lane, dirt road honking around each blind corner and hoping no one was coming the other way. I felt an openness to the universe, to my own morality and immortality brought on through not only the accomplishment of Jebal Toubkal but also the cultural, geographic whiplash of the past days. The Magnificent Seven poured out through the car’s battered speakers, far below I could still see the destructive signs of the flash flood that had torn through the area widening the riverbed. The unprotected shoulder of the mountain road and the long fall beyond it just past window as I hung my arm out in the sun. The driver smiled and gave me a thumbs up in reference to the tape. The opening to Hitsville U.K. like far away news of the world. When we reached Marrakesh I let him keep the cassette. What have we got? Yeh-o, magnificence.

Sandinista! is a humanist, populist record, more so than any they’d done before or any I can think of by anyone else. The Clash never stopped being four working class kids who never forgot the toll this world takes on ordinary lives. Sandinista!’s message is about the high human cost that the post-colonial, raging Cold War, neoliberal world of that time was exacting. Unlike so many other punk bands (then and now ) who will just angrily (and somewhat academically) lecture you about a circumstance over a four four beat; The Clash put you into the situation with a poetry and an attention to the details of the experience so that you’d have to reckon with it if you were paying attention. Subversion through empathy. It’s like how Fast Car by Tracy Chapman does more to explain the reality of the cycles of poverty than any university class or paper ever could.

Along with The Magnificent Seven, songs like One More Time, Up In Heaven (not only here), Somebody Got Murdered, Broadway, all dealt with the ravages of the class system that they had witnessed first hand. Up In Heaven was speaking specifically to the shitty living conditions the poor and working class were subjected to in London, but it’s delivered in a visceral way that’s applicable most cities throughout the world. When I listen to it now I can’t help but think of a movie like Parasite or so many hip hop songs from the Nineties. How art like that can look at an experience that is usually ignored or at best just a reductive setting for a police drama and convey the unspoken, three dimensional human experience.

The towers of London, these crumbling blocks

Reality estates that the hero's got

And every hour's marked by the chime of a clock

What you gonna do when the darkness surrounds?

You can piss in the lifts which have broken down

You can watch from the debris the last bedroom light

We're invisible here just past midnight

Strummer wrote Broadway about a homeless man he encountered again and again outside his home. Somebody Got Murdered is the result of Joe coming upon the body of a parking attendant lying in a pool of blood, he had been murdered for only a bit of change. He couldn’t find the man’s name and later wrote the line “Somebody Got Murdered” which Mick then wrote lyrics about. Memorializing the way desperation preys upon the prey in one of their best songs.

Somebody got murdered

His name cannot be found

A small stain on the pavement

They'll scrub it off the ground

After that dream I always traveled with a copy of that album with me, like a talisman. Throughout the states, Mexico, South America, Europe. I heeded the dream and found that it basically informed everywhere I went in a subtle but pervasive way. Going beyond the local economics of a city or a country. I saw the outcome of some of the places destroyed by the proxy conflicts of the Cold War. Conflicts I was not taught about in school but learned of only through music. The Clash took a strong anti-imperialist stance during a time when the world and most conflicts were divided along the ideological lines of the US or the USSR. In Washington Bullets they literally name check multiple, horrible proxy wars and their roots in a single verse. The US in Cuba and Nicaragua; Russia in Afghanistan; the Chinese in Tibet and the British mercenaries throughout the developing world. All profiting from war, weapons and misery. It’s a call to choose people over politics. Joe walks you into the song from the perspective of a mother watching her children play in the street, just wanting them to be safe. Not knowing that a 14 year old was just shot in those streets. Maybe it’s the Cancer rising in me but those lyrics grabbed me and have never let go. The grip only tightens on my heart in a later verse when he sings about Pinochet’s Chile; the torture and the death squads and pleads:

Please remember Victor Jara,

In the Santiago Stadium,

Victor Jara was a Chilean director, poet, songwriter and political activist. His work focused on love, peace and social justice. When Allende’s government was overthrown by the US backed Pinochet, Jara was arrested and brought to the converted Santiago Stadium along with thousands of other political prisoners. There the guards tortured him, then smashed both of his hands and mockingly told him to play his guitar. Instead he burst into the Chilean protest song Venceremos. They shot him over 40 times and dumped his body in the streets of a local shantytown. The contrast of brutality of his death and the spirit of his life led to him becoming a pivotal symbol of the resistance to Pinochet’s facism and US imperialism. When I hear the words please remember Victor Jara I can’t help but feel all the weight of this request. Not only should he not be forgotten, he should be more widely known. We have to remember those who dare to work for something better and are destroyed for it. It’s the weary sincerity of the“please” that stays with me.

Joe

My experience has taught me that the great battle of our time is against dehumanization. It’s resisting the massive amount of money, effort and misery that the status quo will exert to wear you down and burn you out until you begin to see other people as “less than human.” It’s the currency of slavery, racism, xenophobia, economic injustice, labour exploitation, policitcal partisanship, sexism, homophobia and all of the rest. To persuade you that “your enemy” doesn’t want a safe home, food for their family, healthy kids and basic dignity. To convince you that their suffering, grief and heartbreak are somehow felt differently than yours. A scam to prevent the global bbq and block party that we have the potential to be. That’s what this record is ultimately about, what it stands for: “Without people you’re nothing.”

I carried all of it with me. Listening while going slowly insane working and commuting to menial jobs throughout the winter; or out wandering some random street in Cochabamba or something. It pushed me to engage the reality of the lives around me or in another land. Eventually, in Riobamaba Ecuador I got the word tattooed on my calf, like some sort of pledge or promise or something. A way to acknowledge the impact and remember. It was less something I intellectually understood and more just an intuition of the spirit, not unlike what I’m writing here. To be honest, I’m having a hard time wrapping this up because there’s so much more I want to say, so many stories that haven’t been touched on, (Mikey Dread producing, El Salvador leaflets being dropped during shows, the spliff bunker, Bankrobber being cut from the album). It’s kind of fitting that I’m finding it incredibly hard to concisely explain all of my feelings about an album that itself is accused of being too meandering, unfocused and all over. That’s this piece, that’s life.

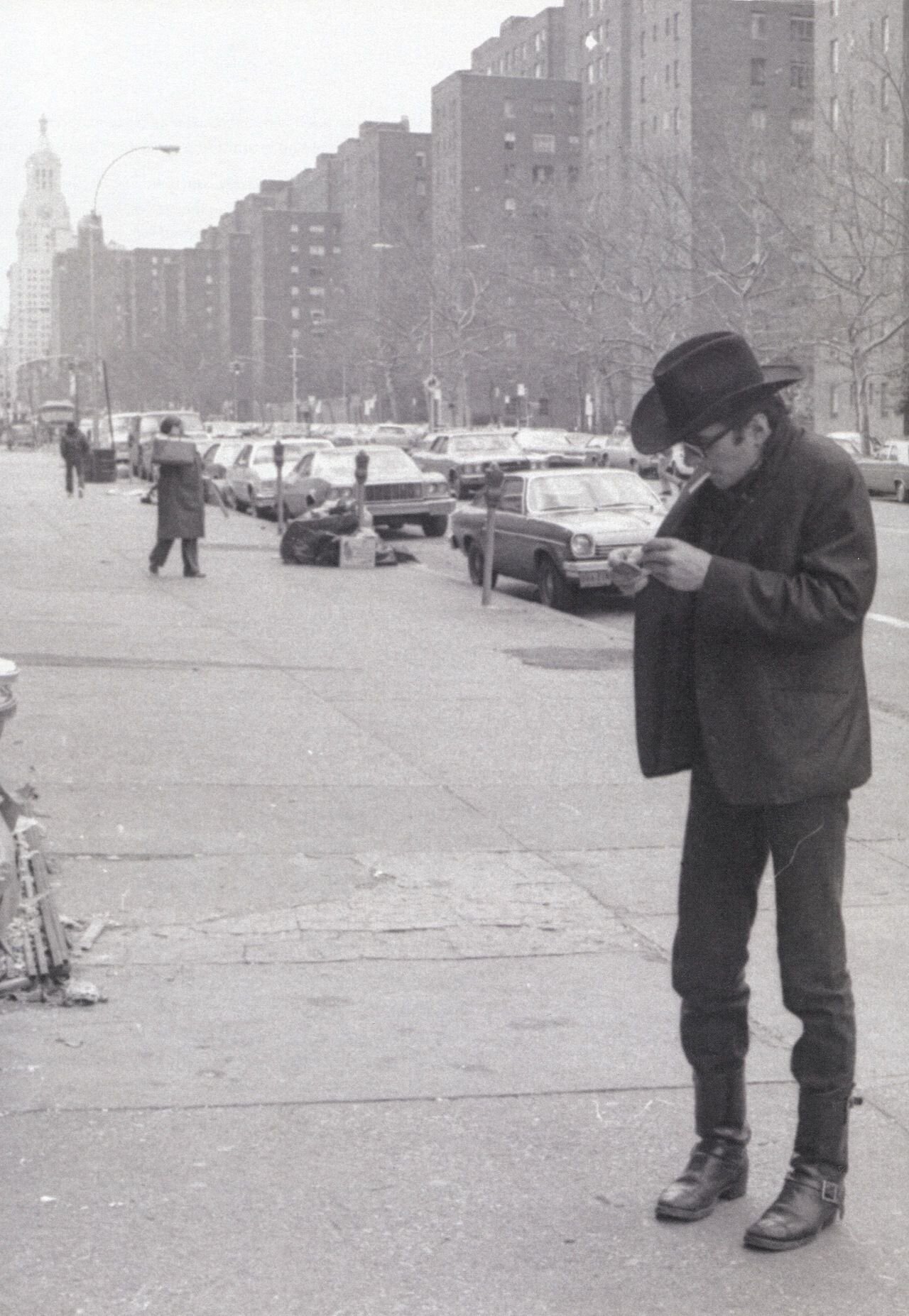

New York-1980

I’ll close with The Street Parade. Almost the last track on the album and one it’s of the most beautiful. Though six songs follow it in my mind it’s the proper ending of the record. Like how this started and like so much of the album, it’s connected to the night. It’s a slow, lonely walk through a jubilant and boisterous crowd. The feeling of isolation even though you’re surrounded by people. Like being a transplant, an immigrant, a traveler in another country and slipping into the crowd as a way to heal or maintain. Wanting to express something but not knowing what to say or even having the language to say it. Sandinista! is multiple stories from multiple village and city streets throughout the world. It’s only fitting that it’s creators would find themselves at the end of all that rage and reveling walking in the evening through the confetti, beneath the fireworks, past the passed out. In love with the world while simultaneously heartbroken by it. I think that duality is why the record means so much to me all these years later. To love humanity is like holding a muse that simultaneously seduces and horrifies you, and you can’t sever either part of that. It’s the struggle of paying attention and being willing to feel. It’s something I always reckon with mostly at night, through insomnia, drunken conversations with friends, long walks on unknown streets and in dreams. I’m grateful for the mess and the flaws of a masterpiece that reminds you you’re not alone in that struggle. I guess that’s all I wanted to say.

It's not too hard to cry

In these crying times

I'll take my broken heart

And take it home in parts

But I will never fade

Or get lost in this daze

Though I will disappear

And join the street parade

Joe at the Roxy in Boston - Alex, Vicki and I drove all night from Vermont to see him and then drove back just in time to punch in for work.